Dear Bazzers

Chola,

I recently moved into an apartment. For the first time in a long time I am living by myself. A little while ago someone asked me if that was a conscious decision. It took me by surprise because I had never thought of it as a choice with consequences; it just seemed natural to me. The question implied that there was something I wished to discover on my own — perhaps, what I really enjoy, or who I may be.

My apartment has a number of books and some of them ask similarly weighted questions, which I usually leave them to contemplate amongst themselves. Georges Perec has proven invaluable in making a home for them, his witty essay Brief Notes on Arranging One’s Books finally convincing me that neither complete order nor disorder are possible to achieve on the material and intellectual axes of the bookshelf. Not that I needed somebody to instruct me on arranging books, only that it’s nice to know someone has given it as much thought as me.

My neighbour is a book collector, or a book hoarder. The distinction between the two is frankly quite blurred, and is perhaps an aesthetic judgement more than anything. Standing at the door of his apartment I often hazard a peek into his lounge, which contains books piled high on armchairs and coffee tables. The rest of his place is equally messy, with crates of empty glass bottles scattered between cat beds and other random objects. My neighbour regularly tells me how the bulk of his book collection, which is now in storage, was damaged by a small fire. I wonder if his apartment was as disjointed before that incident, which seems to have thrown him into some kind of eccentria. He talks about one thing and then something completely different, misunderstands a question of mine, and generally speaks quite openly with me. He is pedantic and generous.

Perhaps there is something wildly eccentric about collecting books. Nicholas Taleb, in his book The Black Swan, speaks glowingly about ‘Umberto Eco’s Anti-library’, which contained at least 30,000 books, most of them unread. For Taleb the anti-library, or the growing number of books that we have not read (and perhaps will never read), is a reminder of the limits of our knowledge of known things. This is not a remark that should lead us to attempt codifying the unknown, but instead be open to its boundless possibilities. The point is this: that ‘read books are far less valuable than unread ones’.

My neighbour spends a lot of his free time organising his soot-covered books in his storage units, which range from Afrikaans encyclopaedias to essays by musical composers. ‘You name it, I’ve got it’, much like a sales pitch, was the description of his collection; although it is almost exclusively non-fiction and is South African in its leaning. Because he spends so much time arranging his books — à la Perec — I guess he is a book collector and not a book hoarder. Hoarding is like an anarchy of known and unknown things. I like to think that anarchy, as both praxis and ideal, is only wholly possible in books.

I know we share a passion — is it an obsession? — for books, amongst other things. How do you arrange your books?

Yours,

Bazzi.

*

Bazzers,

I will cling to this statement, "Read books are less valuable than unread ones," the very next time I catch myself snooping around on Amazon.

Outside of publishing industry circles, I keep running into pronouncements by 'normal' people that it’s okay to put a book down if it isn't quite turning out to be what you thought it would. I feel like this speaks to several conditions: my perennial one, as an African writer that has to pitch quasi-African stories to overseas parties — as a book-lover that generally trusts but is often underwhelmed by the recommendations of very good literary journals — and as an observer (ahem) of digital society, which continually finds intellectual ways to explain itself out of committing time and attention to anything of real substance.

On that last bit I don't blame people entirely. I think the workplace, the organisation, has evolved into a place where the presumption is that time and not so much labour, not so much effort, is the greatest sacrifice you can make for doing a desk job. Books are such obvious casualties in the battle for our time because they’re not in any programmatic ads: you can't automate yourself into experiencing them the way you can, say, season three of Better Call Saul. You have to pick them up and give a careful, considered shit.

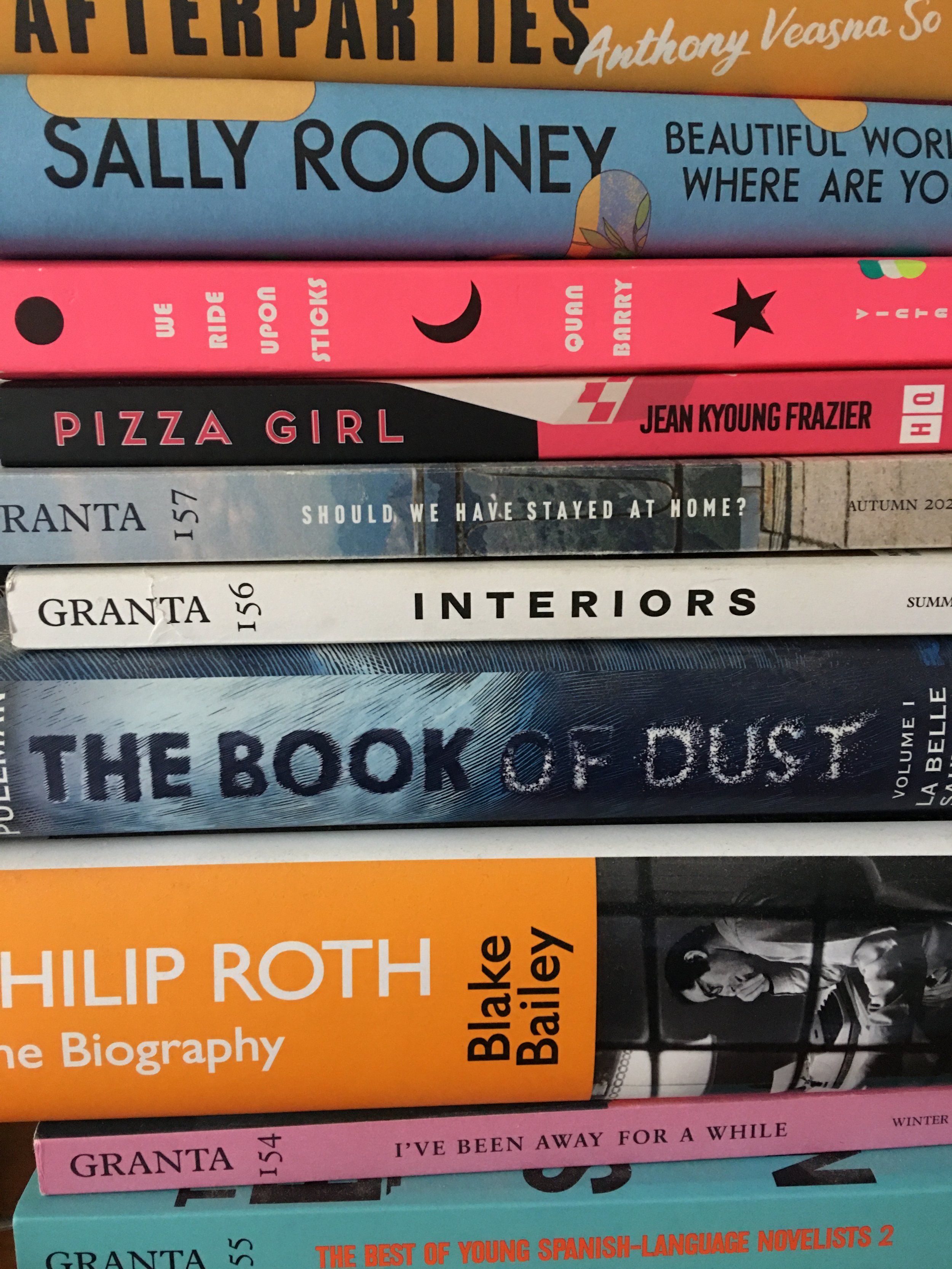

And I don't reference prestige TV by accident. That's a crutch I personally like to lean on; that it’s okay if I've only read half of Beautiful World Where Are You (ergh) because I’m actually committing my free time, post-slog, to intelligent binges. There's validation in there somewhere. I feel like books are such lonely things to dive into, in the dead of night when there is no industrial hum outside my window. Maybe because there’s no one to talk to about the process as you go along, to exclaim by the kettle the next day, "Yo, did you see that?" I want to say I once read half a contemporary debut to Clair De Lune, which sounds pretentious I know but does wonders for an author's dry wit. I have failed, subsequently, to repeat the trick. Not because I can't turn off the Xbox (I can) or there is too much baseball on (there is), but because I can't get my mind to slow the fuck down.

Your neighbour reminds me of a movie I had to stop watching, The Humans, because it said such intimate things — just visually — about how we occupy space as we age or pair ourselves with other people. On the subject of book collecting and/or hoarding, it feels like this is another thing we do to stave off death, to continue to mean something … to keep from hoarding or collecting memories, especially the reasons we're alone, in our brains.

There is nothing in particular I do with my books. I just like them there, in my bag, at my desk, on my table when I used to try to write in breakfast places. To remind me, I suppose this too is pretentious, that we're forced to pay little or no attention now to what really matters.

Cholls.