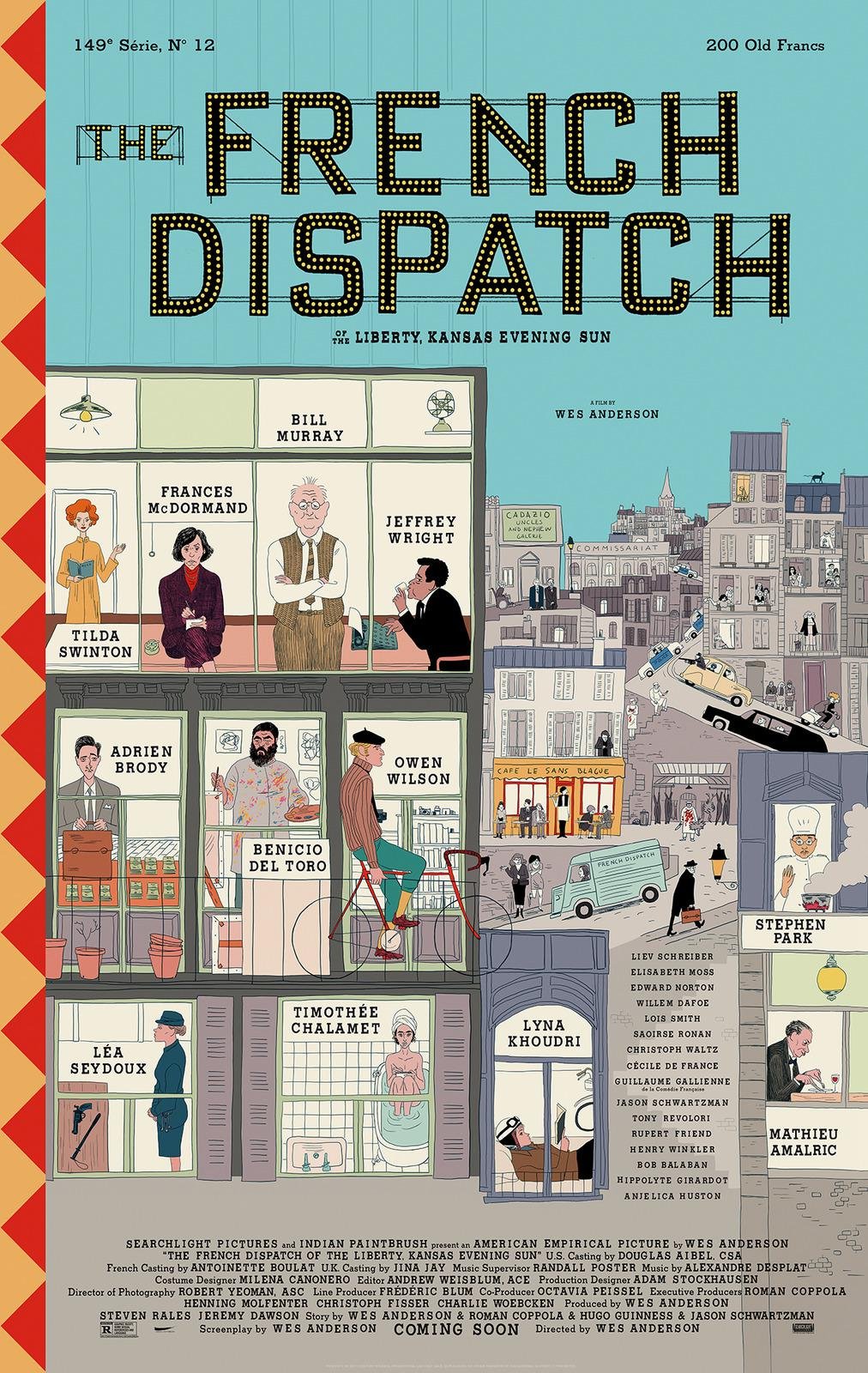

WesFest Day 3: The French Dispatch!

As is my custom, I recently began to read and then abandoned a review about a movie I was super-excited to see. This was a prickly one, for once, by I think Anthony Lane over at The New Yorker. That’s the esteemed journal, no less, that Wes Anderson grew up reading — that Anderson too, perhaps, dreamt might publish his short story and catapult him instantly into literary fame. It’s been a few months, so I’m not going to check if I’ve already said this: but the appeal of Wes Anderson movies is that they sound like such boisterous literary novels, deliberately pumped full of hot air so that Anderson can mock the very pretensions of intellectual superstardom.

Lane’s pseudo-review — and forgive me, Mr. Lane, if it wasn’t quite you — was by no means an ass-kicking. What he levelled against the movie was that by bringing to life a collection of magazine articles, all loosely based on real-life New Yorker ones, the Dispatch is too busy an endeavor; too convoluted to be a project we file in the archives someday as singularly reflective of Anderson’s greatness. I beg to differ. Maybe the pandemic has given this moment in time, and what art we attempt to understand it with, the feeling of starting over. When I first saw the trailer, I remarked to colleagues, Maybe Anderson thinks he’s going to die, or has been negotiating with the idea that his days, or maybe all our days, are finally numbered. Hence all this stuffing for all the turkey that is The French Dispatch, a collection of movies (let’s do that) about a charismatic but grumbly magazine editor who sends the darnedest people to the darnedest places in search of great stories. But then the Internet duly informed me that Mr. Anderson was already hard at work on another picture — I don’t think there were even vaccines yet — and so instead I came in raw, virginal. Somehow assured in the belief that I was accompanying my favourite film director personally into the minutiae of where it all began.

A student protestor vaults out of a bath, notebook in hand, privates shoddily covered, to source the feedback of a Dispatch writer on a manifesto. Uprising tears the city around them into several pieces. When she calls the prose ‘damp’, he asks if she means literally or metaphorically. Both, she says, to which he responds that all he really wanted was affirmation that it was already good. This is exactly the sort of winking, self-conscious egotism that tends to define Anderson’s protagonists, and that the director doesn’t seem to mind you suspecting him of either. Add a proper foil and a love interest, and the bombast of the self-appointed creative demigod is the joke that just keeps on giving, the perpetual punchline that has spawned a cult (‘Wesleyans’?) that I’m proud to be a part of.

Dispatch might seem all over the place when it kicks things off, if only to impress upon the viewer what diversity of mind and life experience Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray, of course) could deem worthy of publication. I hate to use the word ‘pastiche’ twice on the same website, but these are the richest five minutes or so I may ever witness — if film is but a marriage of screenwriting, photography, light, motion, music. It’s as if Anderson is declaring love to several damsels at once, with an electric guitar that’s also a clarinet that’s also an accordion. Once the conceit is 100% clear, that we are to drift between magazine sections, and thus between essays and their eccentric narrators, Anderson finally allows us to take the window seat and buckle up.

I kept waiting for each subsequent ‘story’ to disappoint me in some way, to lack the intrigue or romance or even paint of the one before. There was no such comedown. A food review of stakeout food prepared by a legendary immigrant chef, authored by a James Baldwin-esque savant, veers deliciously right of a student uprising whose hipster civil war, at centre, is not unlike the modern struggle to be on the correct side of ‘woke’. Said hipster civil war, waged purely in the shaky currency of Not Fully Formed Ideas, is preceded by a tragic commentary on how the rich prey on the poor for art, by way of a convicted felon who mesmerises an art dealer in prison, after he is in turn mesmerised by a prison guard who refuses to love him. The very first of these tidbits, ‘The Cycling Reporter’ by one Herbsaint Sazerac (LOLS), about how a city’s true colours are directly proportional to its rat population, is a gorgeous appetiser.

I do have a favourite amongst these short stories, it so happens, even though the writing — Gawd, the writing — is all-round spectacular. In ‘Revisions to a Manifesto’, as above, the Mavis Gallant-esque Lucinda Krementz informs her hosts at dinner that she has neither a husband nor children because they are “the two greatest deterrents to any woman’s attempts to live by and for writing.” All of this while a city rages to the tune of detonating tear-gas and rubber pellets outside, which really is the tune of students needing to rally somehow against an unjust world. Ms. Krementz’ article is a clear-minded journey to pinpoint against what exactly, in amongst the enfants grincheux, and in which Lyna Khoudri (a real-life French actress) illuminates the Anderson experience like few others have before. She never takes her riding helmet off, holds her cigarette the way pioneer actresses did, and rattles her lines off like actual machine gun-fire. Scene-stealing is one thing; scene-marauding is quite another.

Her character, Juliette, is ultra-informed, super-defensive, viper-tongued towards Ms. Krementz and even (real-life) Timotheé Chalamet. There is a moment, illustrating the need of adult youth to align to something, anything, when boy and girl differ on what image ought hang in the coffee-house where they and their peers plot rebellion. Agitating against that of a beloved musician, Juliette outlines (verbatim) that Tip-Top is a commodity represented by a record company owned by a conglomerate controlled by a bank subsidised by a bureaucracy sustaining the puppet leadership of a satellite stooge government. “For every note he sings, a peasant must die in West Africa.” I stood up in front of my computer, on my bed, and applauded you, Wes Anderson.

Before we are launched face-deep into the fantastical conceit of gourmet stakeout food, in the Dispatch’s excellent final story, there is so much literary innovation to behold. The moment Zeffirelli, who will later adorn meaningless T-shirts, referees a quarrel between the world-weary Krementz and the barnstorming Juliette, is old Hollywood joy — the way Chalamet speaks to two characters at once, by pleading with them, and also envelops the setpiece’s cadence about varying approaches to resistance. I bet in a Film class this screenplay would score a B-minus for its drunkenness and dexterity; but my goodness, what a melody it is.

I don’t want to call the format in which the last story delivers its coup-de-grace a cop-out, just because I know what Anderson is fully capable of bringing to life. I’m sure this had loads to do with having to assemble a movie like this, any movie like Anderson’s, within public health restrictions. By then, all the hard work is done anyways. Wes Anderson has woven together tragedy and comedy, crime and caper, some spineless politics and (ahem) such shimmering prose, into the best novel you’ll watch this year and possibly next, and also the best movie you’ll read.

Bra-fucking-vo.